25 April 2013

London

ANZAC Day: a celebration of New Zealand’s national identity, or a reminder of a pointless bloody war and an embarrassing colonial history?

Today is ANZAC Day, a date not observed by the majority of Britons, but a national holiday in New Zealand and a date on which we reenact one of our most enduring and powerful national rituals – commemorating the deaths of all those lost in wartime, particularly from the First World War.

In 1914, New Zealand, as a well-behaved lapdog to the British Empire, sent tens of thousands of soldiers into the First World War. In World War II, our Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage even touchingly declared war on Germany at the same time as Britain did, stating the oft-quoted phrase “Where Britain goes, we go”. Being from the Colonies, New Zealand and Australian soldiers were mostly sent to the suicidal campaigns like Gallipoli, where they were insufficiently armed and tactically outmanoeuvred, and became bullet fodder for the German machine guns. Unsurprisingly, over 18,000 New Zealand soldiers died during World War I, which for a country with a population of less than 1 million was a massive loss. Among the mass fatalities of World War I, New Zealand was the country that lost more soldiers per head of population than any other fighting country.

There are now war memorials to the WWI dead in every town and city in New Zealand, and every year without fail, there are services at dawn, which are still well-attended and publicly televised. ANZAC Day memorial services have been a part of my consciousness for as long as I can remember. (ANZAC Day is also my brother Stephen’s birthday, and I was always envious of him for getting a public holiday for his birthday). What few remaining war veterans there are get wheeled out to attend, usually pushed around by sleepy looking Scouts and Girl Guides, everyone wears a poppy, wreaths are laid in front of the memorials and there’s always a bugle player playing “The Last Post”. Over time, the services have been expanded to commemorate all casualties of war, from World War II, Korea, Vietnam and the Gulf Wars.

As New Zealanders travel, they tend to take their customs with them, and so Dawn Services continue to take place in the UK, and tens of thousands still flock to Gallipoli in Turkey every year to join the annual ANZAC Day ceremony. In 2006, the British Government finally acknowledged the contribution of New Zealand armed forces in the various campaigns of the Empire, and allowed the creation of a New Zealand War Memorial, which sits at Hyde Park Corner, in the shadow of the pompous, imperialist Wellington Arch. The memorial consists of 16 cross-shaped vertical bronze standards set out in formation on a grassy slope. Each standard is adorned with text, patterns and small sculptures expressing something about New Zealand culture and life. It’s one of my favourite pieces of public sculpture in London, and it works so well, I think, because of its simplicity and lack of pretence, and its tiny size being dwarfed in the shadow of the great English architecture around it. It’s a fitting metaphor for New Zealand’s relationship to Britain, and the way in which New Zealand’s contribution to wartime efforts was overlooked by the Empire.

The UK equivalent is, of course, Remembrance Day (formerly called Armistice Day) on 11 November 2010, which is elevated into a similarly powerful national ritual. People wear poppies for weeks before and after (sold to benefit war veterans’ charities), the commemoration services are attended by the Queen, and every November there’s usually a flurry of war documentaries and re-analysis of the great work of War Poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

Remembrance Day is the closest thing England seems to have to a unified national ritual, and the only holiday that the English appear to be able to get through without being embarrassed or apologetic about what they’re doing. Unlike Ireland, France and most other countries in Europe, England has no single national holiday where it celebrates its country. St George’s Day, which was just 2 days ago, is England’s patron saint’s day, but seldom gets celebrated and with nowhere near as much fervour. It’s fair to say that most sightings of the St George’s Cross these days tend to signify skinheads, white racists and far-right wing organisations like the British National Party, or at least football hooliganism. All that anxiety and ambiguity about Englishness melts away on Remembrance Day, albeit temporarily, with an accompanying relief that England has something it can celebrate with consensus and a minimum of hand-wringing .

In her very entertaining missive on the decline of modern manners, Talk To The Hand, Lynne Truss writes with a palpable sense of relief about the deference and public respect shown to Remembrance Day:

“What is left of pure deference? In Britain, I think the last thing we do well (and beautifully) is pay respects to the war dead… The controlled emotion of Armistice Day tugs at conscience, swells the commonality of sorrow, and swivels the historical telescope to a proper angle, so that we see, however, briefly, that we are not self-made: we owe an absolute debt to other people; a debt that our most solemn respect may acknowledge but can never repay. We stop and we silently remember… The first cannon fires at 11am, and one is overwhelmed by a sense of sheer humility, sheer perspective. We are particles of suffering humanity. For two minutes a year, it’s not a bad thing to remember that. If we looked inside ourselves and remembered how insignificant we are, just for a couple of minutes a day, respect for other people would be an automatic result.”

She goes on to comment, “It is a miracle that some sort of political relativism has not contaminated this ceremony of public grief, a full sixty years after the end of the Second World War.”

Like Lynn, I continue to be amazed (and rather moved) that, 90 years after World War I. It’s extraordinary to me that after years of a pacifist rethinking of war and war imagery, ANZAC Day and Remembrance Day is still such a sacred ritual. This could be due to the distance in time between WWI and the present times, now almost a century ago, a period that now seems as remote and romantically charged from our own times as an E M Forster novel. There’s something comforting, I suppose, about a time-honoured ritual, especially for a young country like New Zealand that only got built last Wednesday and is still negotiating its own sense of national identity.

That being said, I get profoundly irritated by the jingoistic crap that continues to be spouted at war memorials about soldiers “making the ultimate sacrifice for their country”. I also continue to get irritated at the mostly complete absence of a dialogue in the UK celebrations about the contributions of the many many soldiers sourced from Commonwealth, and the lack of any general knowledge in the British population about the less attractive aspects of British rule under the Empire.

As a product of the pacifist generation, or possibly as a result of reading too much war poetry, I’m of the conclusion that World War I was an enormous balls-up – a quarrel between spoiled imperialist powers desperately trying to hang onto a rotting social structure that deserved to be thrown out anyway, resulting in a colossal and pointless loss of life. The “sacrifice for your country” (or, in the ANZAC’s case, the “sacrifice for the Empire”) was sold as a useful piece of propaganda to encourage soldiers to enlist and keep the populace on side to support the war effort, and to give grieving families some sense of comfort that their sons and husbands hadn’t been butchered for nothing. It’s an understandable enough intention, I suppose, but it’s also military propaganda at its most insidious: to appeal to a greater social good as a way of justifying mass death and deflecting the very real possibility that those deaths were unnecessary and meaningless.

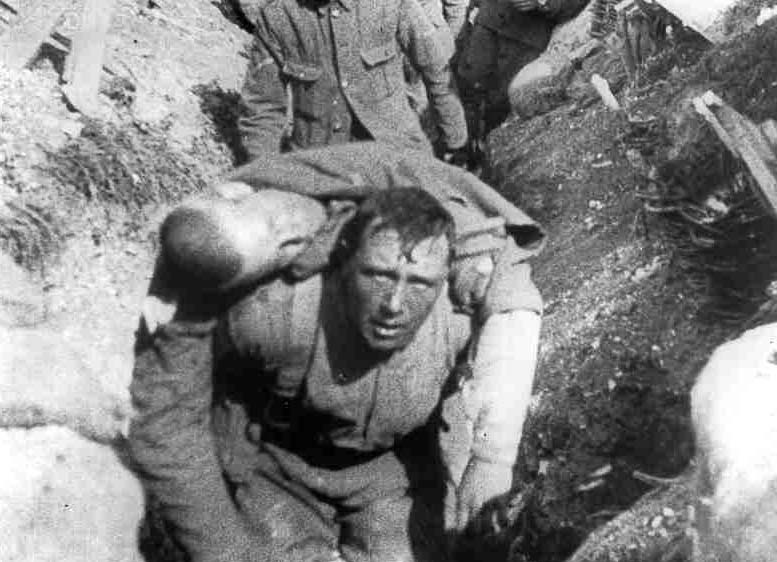

My favourite image of the World War I campaign is Stephen Fry playing Lord Kitchener in Blackadder Goes Forth, inspecting a map of the war campaign dotted with toy soldiers, then sweeping most of them off the map using a halfbroom and shovel and tossing them aside. This seems to summarise – wittily, but with a bitter taste in the back of the throat – how appallingly organised the British campaigns were, how thoughtlessly hundreds of thousands of foot soldiers were sent into battle with inadequate arms and little training, and how decisions were made by English aristrocrats with no military training who’d bought a regiment and were living out some kind of Rudyard Kipling fantasy of England and Empire. Hundreds of thousands of teenage men were sold that fantasy, and rode off to war imagining it would be over in three months and in the meantime they’d see the world and have adventures. What they got instead was en masse slaughter, the filth of trench warfare, gas attacks, shrapnel wounds, amputations and psychological scarring that’s still working its way through subsequent generations. It was a bloody, angry mess.

Despite this, the dominant cultural narrative of war commemorations continues to be dewy-eyed nostalgia for the Great War. New Zealanders have an especially patriotic view of World War I as the moment in history where we distinguished ourselves on the world stage, demonstrated our bravery and loyalty to the Mother Country and earned the right to our independent nationhood. Even our nickname as “Kiwis” is thought to derive from the army boot polish used by soldiers at the time, which featured a picture of the Kiwi bird on the tins. It’s a truth well-observed that nationhood is often born via conflict. To me, this romanticising of our wartime history still smacks of propaganda or the need to make a senseless situation make sense because the alternative is too painful to face up to.

War being what it is, it certainly shook things up, and as we know, war did reverberate through society in interesting ways. The mass departure of men had a huge impact on the social status of women, who finally got out of the kitchen and into the workforce – even though they were chased back into domesticity in the 1950s. Military service aided a number of men in finding out about same-sex attraction, which I’m thoroughly in support of.

I can’t, however, listen to another puffed-up public official spewing out tired clichés about bravery and sacrifice and national values. This is a fallacy. I don’t doubt that the men and women who died in the Great Wars were brave, and I’m sure many of them thought that they were fighting for a greater good. I’m also fairly sure that many more of them had no idea what they were getting themselves into and died terrified and in despair, and considering that the greater good was just political puffery created by their uncaring overlords. It’s this continuation of the need to push the heroism narrative above all others that makes me no longer wish to attend war commemoration ceremonies. I’m happy to pause and acknowledge the massive loss of life, and consider the futility of war, and consider my own good fortune about never being called up for military service. But for me, that’s where it ends.

So this ANZAC Day, rather than hauling myself out of bed before dawn and going to the ceremony at Hyde Park, I’m baking Anzac Biscuits, listening to Britten’s War Requiem, and rewatching the final episode of Blackadder Goes Forth, Gaylene Preston’s wonderful documentary War Stories (Our Mothers Never Told Us) or maybe Derek Jarman’s divine and very under-valued experimental film War Requiem. Until then, I’ll leave the last word to Wilfred Owen, the great poet of World War I, and his masterwork “Dulce et Decorum Est”. The resonance of his work is stronger in the knowledge that he died just a week before the Armistice was declared. It’s interesting to speculate on what he might have added to the dialogue about war had he lived. As he didn’t, we’re left with his poetry, which expresses the horror and futility of war and quashes the myth of “For King and Country” powerfully than anyone else ever has, then or now.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

(Written 8 October 1917 – March, 1918)

Another fascinating piece that gave me a lot of food for thought. I think Remembrance Day is more complex than you and the admirable Ms Truss suggest. Is there anything to celebrate about the destroying of a generation? How can one take pride in a country that so carelessly kills its young (and, as you point out, even more unforgiveably, the young of other countries)? I think there are a whole lot of embarrassing questions going on underneath the ceremonial that make it a profoundly tense and uneasy occasion. There is a very uneasy (not to say passive aggressive) truce going on where the Government is forced to acknowledge the loss of life it ordered in return for no-one actually being held responsibile for it, whilst the generation who were sacrificed are given the possibly false consolation of imipressive ceremonial and the suggestion that there was value to laying down their lives provided that they don’t ask any awkward and challenging questions (those injured in existing wars are never allowed to join the parade, and survivors with disabiliites have tended to be sidelined Interestingly, it’s always the First World War that defines Remembrance Day, when the betrayal of generation by a public school establishment – very much David Cameron’s predecessors – was most appallingly pointless. The second world war did at least bring the holocaust to a halt. And of course the waste of the flower of a country’s youth continues via unemployment: lions led by donkeys. At least the establishment are made to feel uncomfortable for a couple of minutes. We can but hope there will be opportunity for a deeper examination when we commemorate – celebrate is SO not the word – the 100th anniversary of the first world war next year

The war was also the subject of well-known poetry, most notably by Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon , both of whom served in the war (as did Remarque). Another notable poem is ” In Flanders Fields ” by Canadian soldier John McCrae , who also served in the war; it led to the use of the remembrance poppy as a symbol for soldiers who have died in war.

Reblogged this on From the Choirboy Motel and commented:

A piece I wrote for ANZAC Day 2013 which I’m proudly recycling for Britain’s Day of Remembrance.